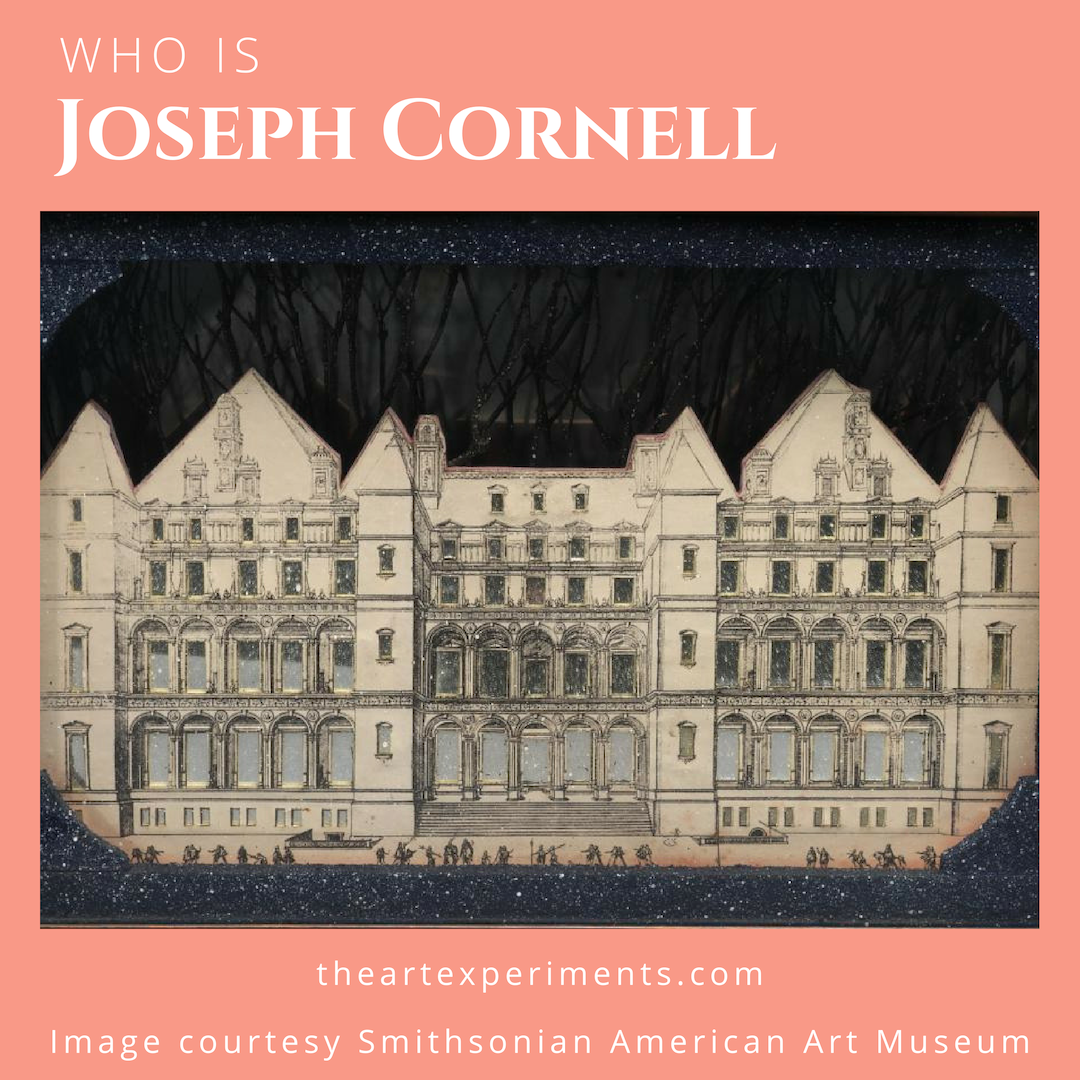

In 1932 Joseph Cornell, an extremely shy artist with no formal training or connections, broke into the avant-garde Surrealist art scene in New York City with his magical shadow boxes, film, and collages.

Cornell was an introvert – to the extreme – in an era of larger-than-life artists like Jackson Pollock. He devoutly adhered to Christian Science while other artists adopted a “bohemian” lifestyle. He worked at regular jobs for most of his life. He had no formal training as an artist. He lived with his mother and cared for his brother, Robert, who had cerebral palsy.

So many things I’ve read about Cornell cast him as an unhappy person, resentful of his mother and brother, whose life was narrow, lonely, disadvantaged and full of anxiety. I hate all of these descriptions given to him! He probably felt all of those things to a degree. Some, probably to a great degree. But, he also had deep and fulfilling relationships. He loved his brother, Robert. I don’t think it was a one-sided relationship with Joseph only caring for Robert. Robert is described as a pretty happy person. Cornell felt obligated to care for his mother and brother, but that does not mean there were no rewards or reciprocity. Also, to say he was disadvantaged during the Great Depression is laughable! He had food, a place to live and a job (usually). It seems like he was doing pretty well!

Cornell did have a small life. He hardly traveled outside of New York. He went to work, to the theater, to church, wandered second-hand shops and art galleries and went home. He liked to look and to read and to think. He was anxious about interacting with people he didn’t know. He didn’t seem to have friends.

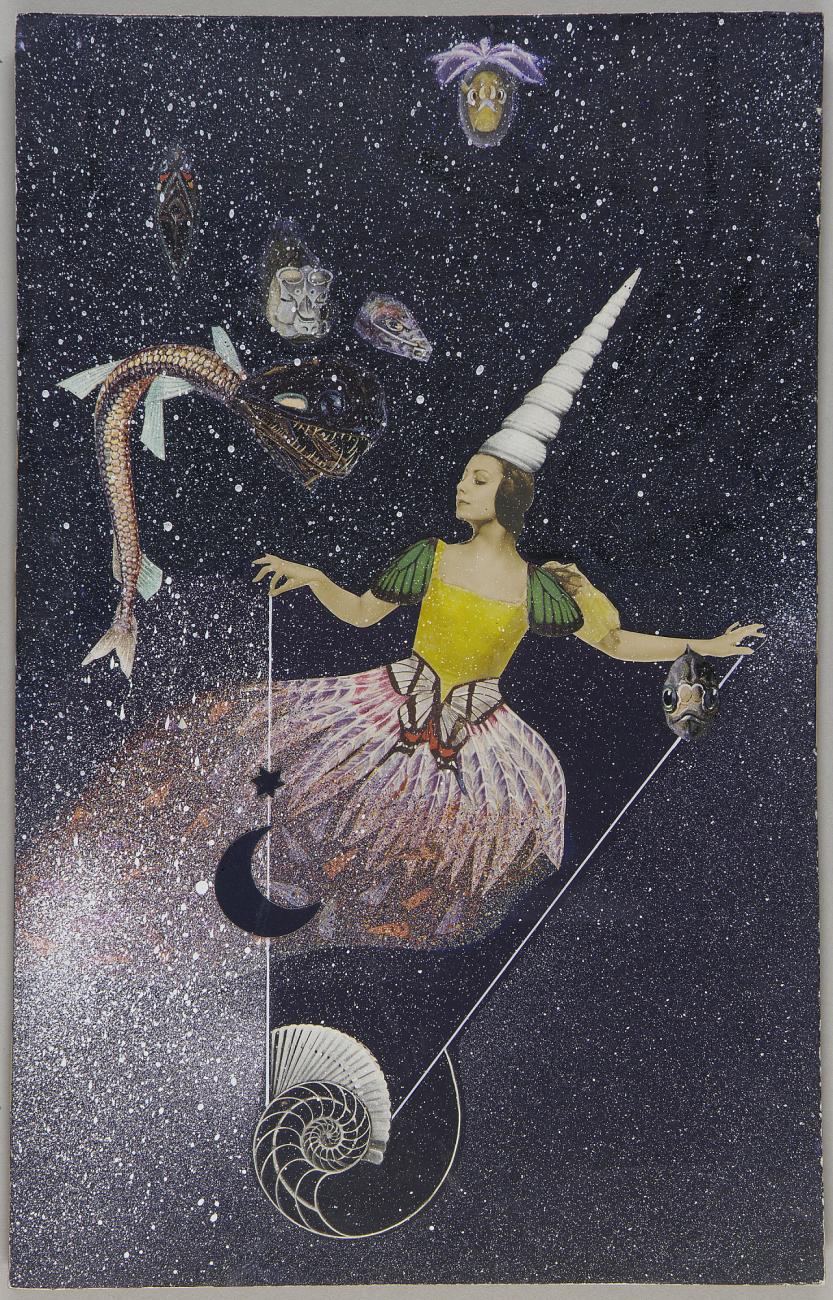

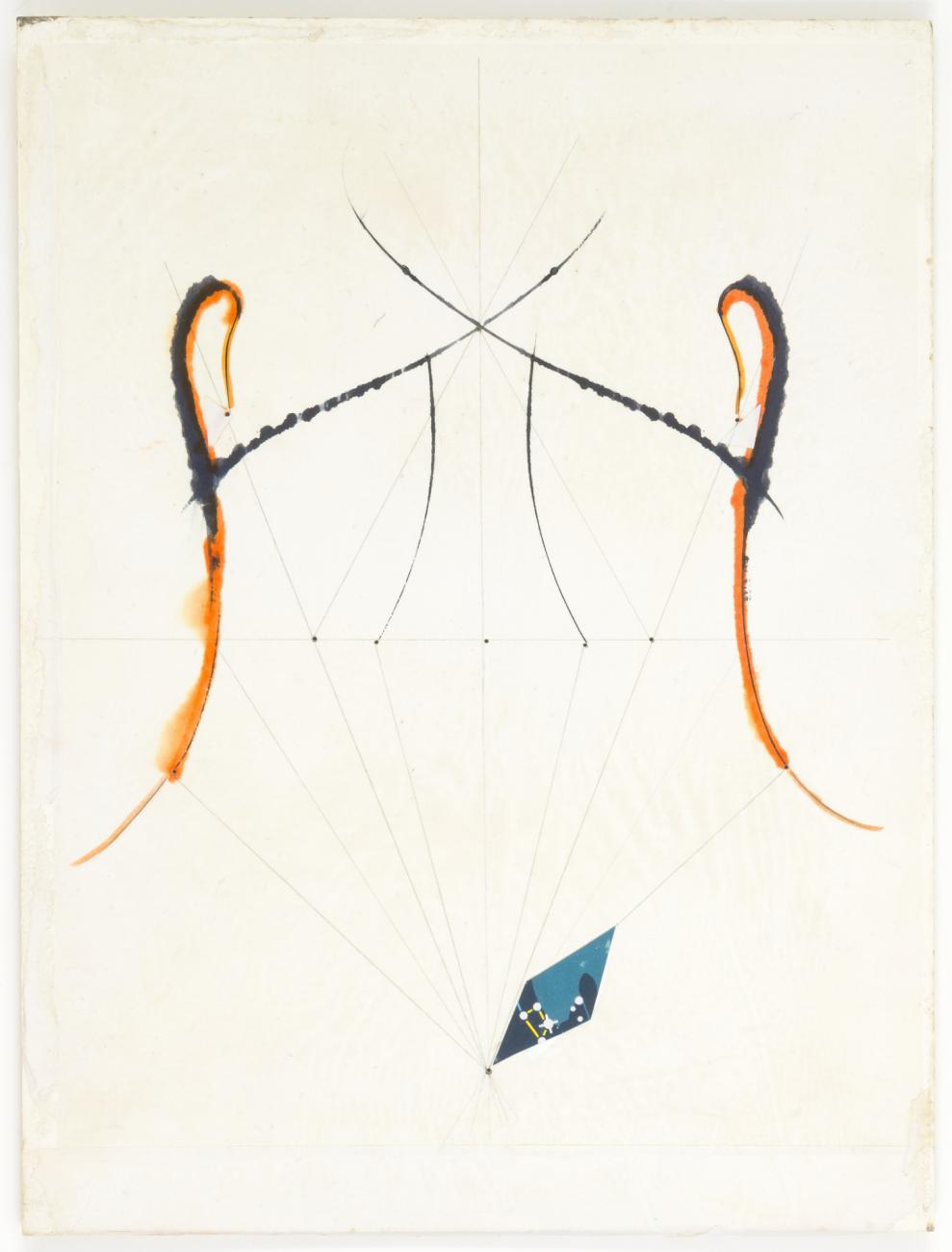

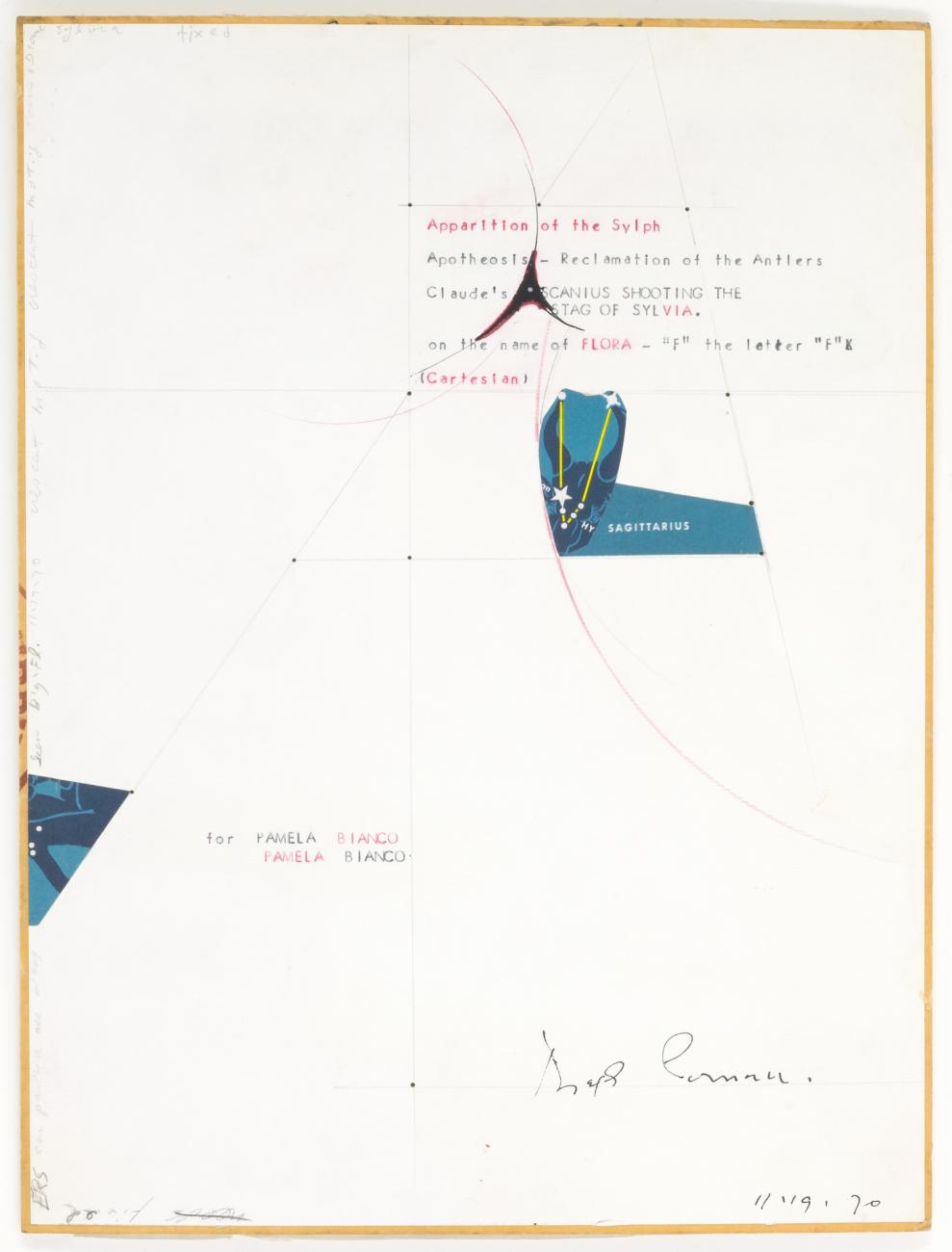

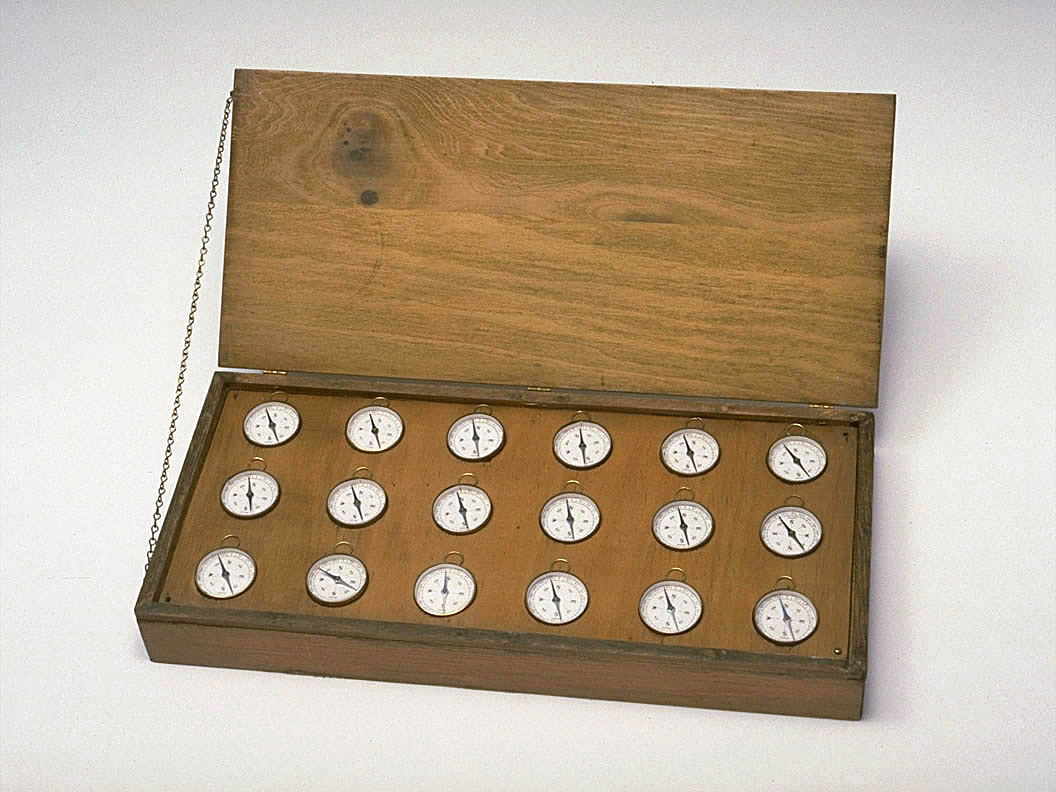

However, he happened on a book of collages and started making some himself. Even as a timid foreigner to the art world, he submitted a few pieces that were included in the first Surrealist art show in the United States in 1932 at the Julien Levy Gallery in Manhattan. From there he continued to experiment with various types of collage – from collages on paper and masonite to assembled pieces inside of minuscule pillboxes or larger boxes he had made. He also made Rorschach-like ink blots and even film.

Cornell didn’t call himself an artist. Since he was never formally trained as an artist, he didn’t feel qualified to call himself one. He especially shied away from being called a Surrealist. Although his art was exhibited with Surrealists and shares commonalities (dream-like, collage, assemblage, pairing things that didn’t seem to go together), he didn’t like some aspects of Surrealist philosophy. André Breton defined surrealism as, “Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation.” Cornell was morally preoccupied. Unlike other Surrealists, his art also has a childlike lightness.

In spite of his shyness, lack of training and lack of opportunity, Cornell eventually became successful enough to have other artists work for him. He made friends with renowned artists and even inspired jealousy in at least one other artist. Reportedly, when Salvador Dalì saw Cornell’s film Rose Hobart in 1936, Dalì upset the projector claiming to have had the idea first.

He also developed a deep friendship with Japanese artist, Yayoi Kusama, who he met in the 60s. Once his mother poured water on them (Cornell was 25 years older than Kusama) when she saw them kissing in the garden. Even when Kusama returned to Japan, they made collages and boxes for each other until his death in 1972.

Cornell’s life, like his artwork, seems to be small in so many ways, and yet remarkable.

All images courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum

Leave A Comment