I love Alexander Calder! He is my favorite. I love his whimsey and playfulness and balance and beauty and versatility. His art is the truly joyful, funny comedian instead of the mocking seventh grader.

For example, one of my favorite parts of Calder’s Cirque is after knocking the acrobat off of the swing, he uses his fingers in place of the acrobat to walk off of the net. It reminds me of my kids playing. That kind of imagination and play is something I’ve lost as an adult. (He once joked that he gets a lot of fan mail, all from six year olds). Anyhow, for me, his art has a purity and wonder that some art lacks.

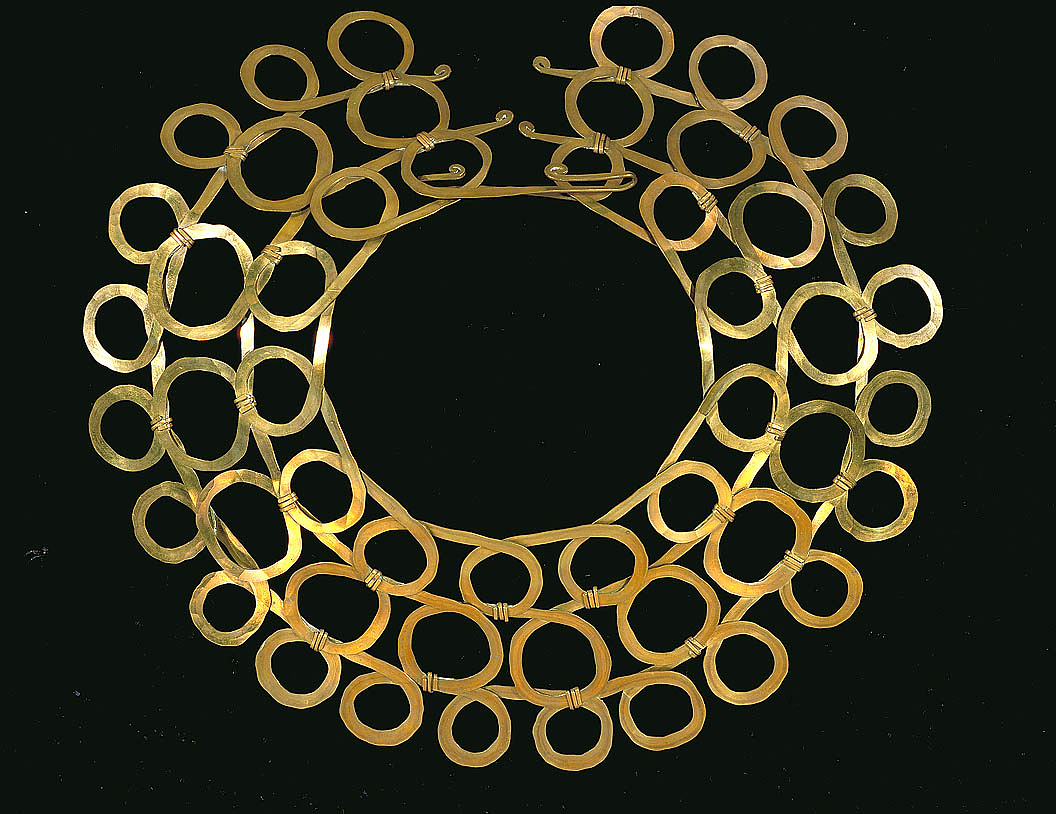

As a child, Calder made toys with moving parts as gifts and jewelry for his sister’s dolls. Although both of Calder’s parents were artists and had created studio space for him in their houses, they did not want him to be one. So, Calder chose to get a degree in engineering. After working at various engineering related jobs, Calder returned to New York to study at the Art Students League.

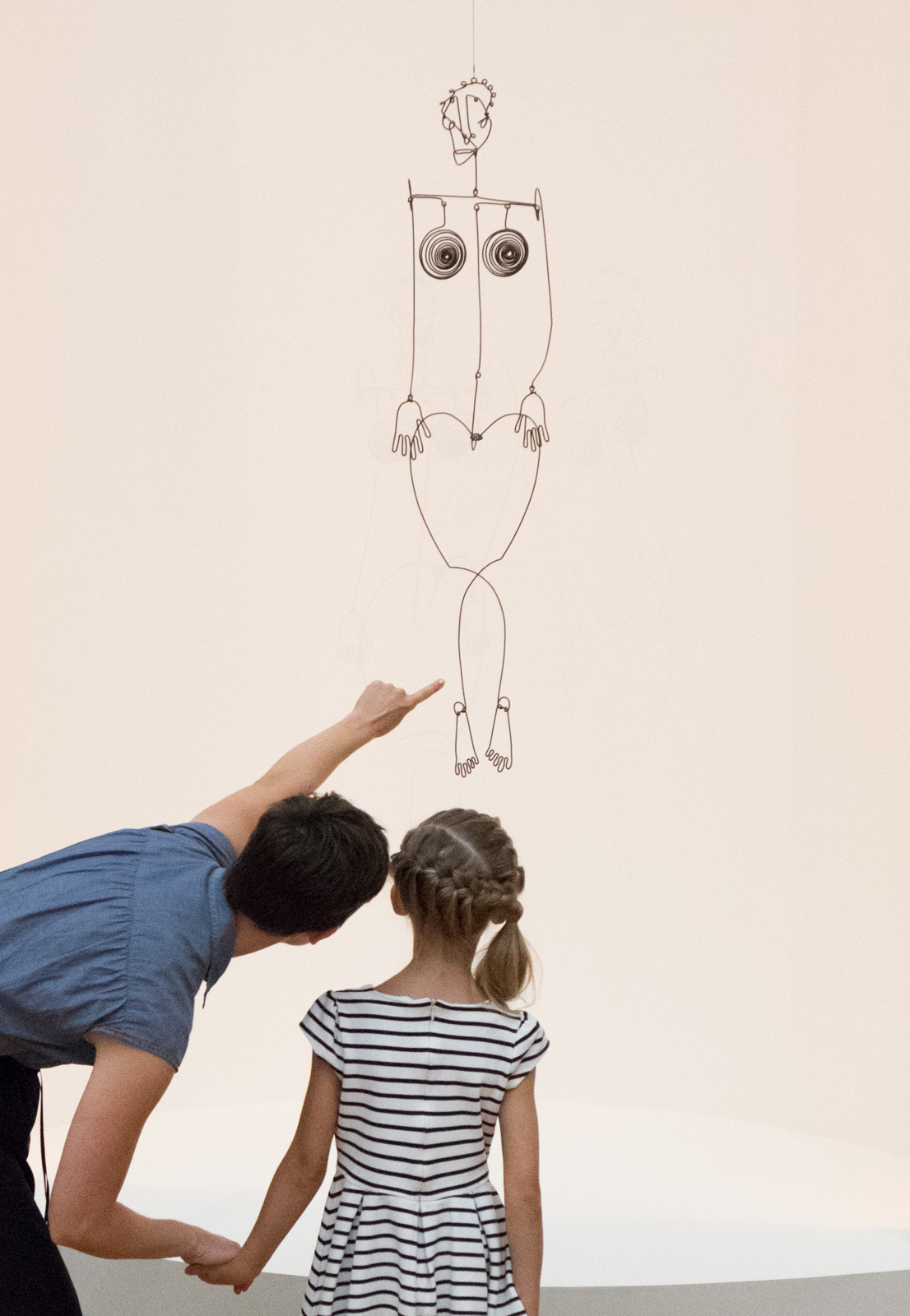

From New York he moved to Paris in 1926, meeting his wife along the way. He and his wife returned to the US in 1933. While in Paris, Calder created mechanized toys and wire sculpture (“drawing in space” he called it) and his famous Cirque. He visited Mondrian’s studio and was drawn to his abstract style.

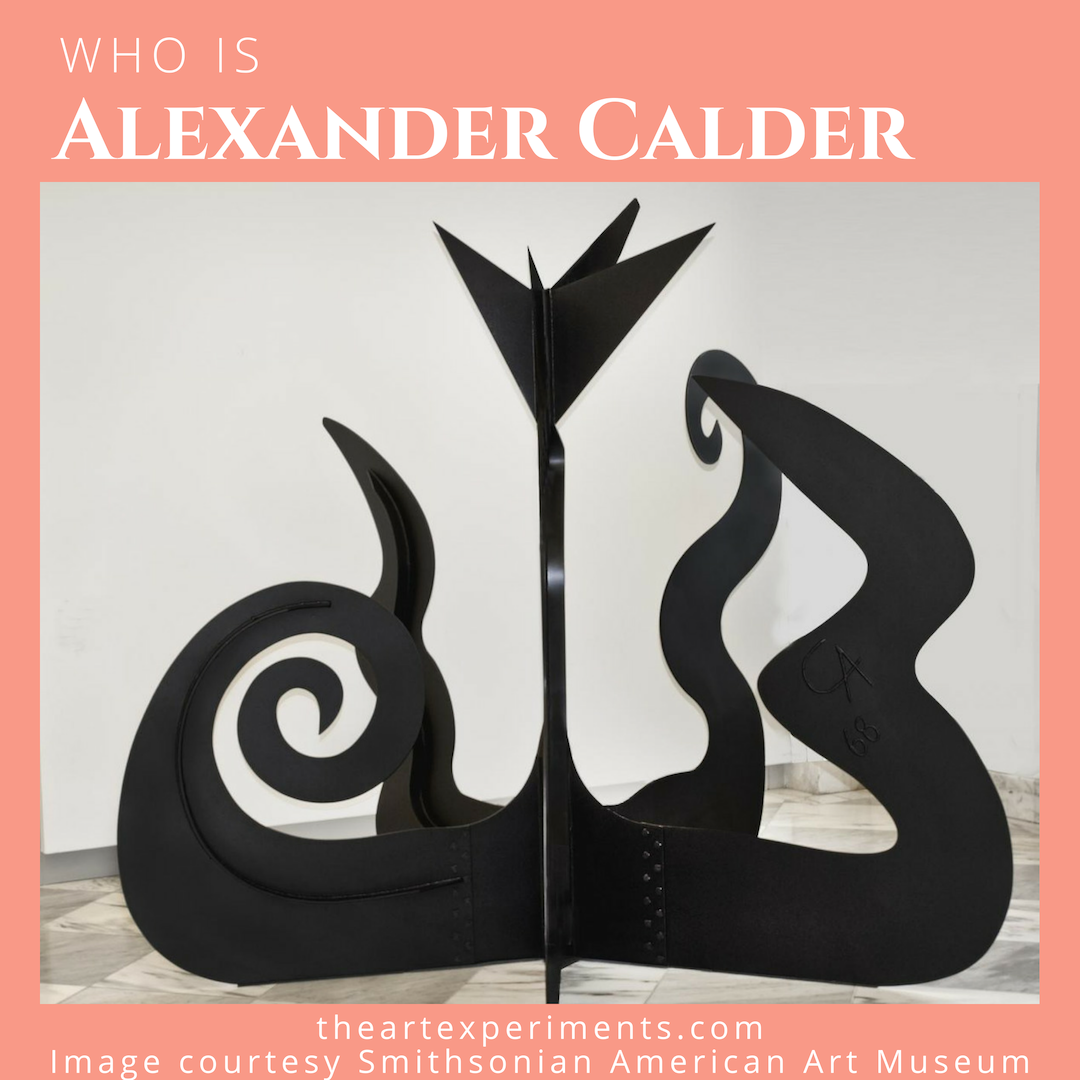

Image courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum

Seeing Mondrian’s work, Calder was led to ask, “Why must art be static? You look at an abstraction, sculpture or painted, an entirely exciting arrangement of planes, spheres, nuclei, entirely without meaning. It would be perfect, but it is always still. The next step in sculpture is motion.” Calder took that step and created mobiles – kinetic sculpture.

His first mobiles were powered by motors or cranks. To increase the variety of movement and to create an aspect of unpredictability, Calder made mobiles whose motion came from the wind. Calder also made stabiles. By any other artist, it would be called a sculpture. A “stabile” is a Calder sculpture without any moving parts.

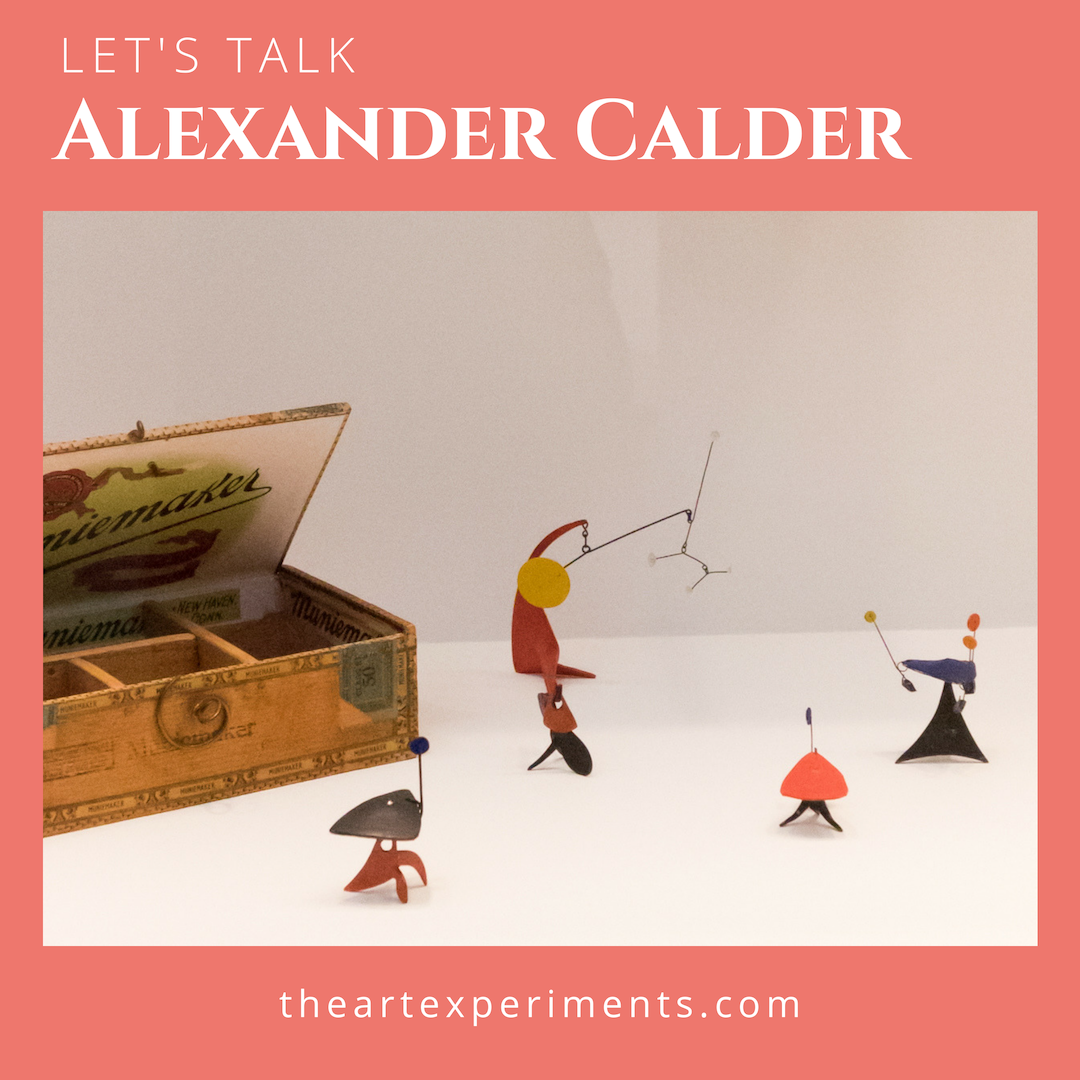

Although Calder’s exhibits were successful in terms of interest, he didn’t make much money from his art until around 1958 when he was commissioned to create large-scale pieces. After that it seems he was in demand for almost anything – from stage sets to book illustrations to painting airplanes. He even created what he called a ballet, featuring his mobiles and stabiles.

Image courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum

The National Gallery of Art has a room dedicated to Alexander Calder. Seeing so many of his pieces together helps in understanding his versatility in using whatever medium is available (during WWII he used wood since metal was scarce) and the scope of what he could create. There are sculptures ranging in size from figures about the size of a chess set to a mobile (in the atrium) that weighs 920 pounds and is about 30 by 96 feet.

Image courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum

If you are interested in reading more about Alexander Calder, here is his obituary from the New York Times. Calder also wrote an autobiography: Calder: An Autobiography

Leave A Comment